GESTINGTHORPE 'THEN & NOW' PHOTOGRAPHIC BOOK - COMING IN 2026 - hopefully!

'Bringing our past to life' by Ashley Cooper

Gestingthorpe Roman villa

Gestingthorpe Roman Villa lies mid way between both, Halstead and Sudbury, and the Rivers Colne and Stour. In this article Ashley Cooper tells of the site’s discovery, before describing the finds and relevance of a Romano- British settlement that was at the heart of our area almost two millennia ago.

My Father, Harold Cooper, moved to Hill Farm, Gestingthorpe in late 1945. One Field – situated on the farm’s best soil – was infested with weeds. Kale was planted as a ‘cleaning crop’. But after harvesting the kale seed, the stalks were too thick to ‘plough in’. A ‘deep digger’ plough was consequently hired from the War Agricultural Committee.

Visiting the field to check on progress, after it arrived, Harold was struck by the vast amount of red tile that the plough had brought to the surface. None of it matched that on local houses, or resembled anything made at the nearby Bulmer Brickyard. Eventually he took a sample to Colchester Castle Museum, where the curator, Rex Hull, identified it as Roman. Impressed by Harold’s keen interest, Rex then suggested that Harold should conduct a ‘trial excavation’. Major Brinson of the Essex Archaeological Society provided invaluable guidance.

For the following twenty eight years Harold devoted every spare Saturday and Sunday afternoon to slowly excavating a series of Romano-British buildings and ditches, together with a ‘hearth site’ and an agricultural area. It was a mixture of hard manual work and meticulously patient trowelling. The ‘geo-physical’ apparatus used by archaeologists today had not been invented and metal detectors were not commercially available. Occupation layers were sometimes a metre or so beneath the surface. Every single crumb of soil – amounting to several hundred tons – was moved by hand. Progress was often hindered by weather conditions: droughts when the top soil was rock hard; wet winters when numerous bucketfuls of water had to be ‘baled out’ of the excavation trench before any archaeology could begin.

Excavation trench to reveal the villa’s flint foundation walls. (They measure approximately 0.8 metre in width.) The trench curves where the semi-circular room begins.

During the first two centuries of Roman rule they purchased smoothly glazed Samian pottery from Gaul – with twenty four fragments providing the makers names. But decorated pottery from Oxford and the Nene Valley, and ‘lipped’ ware from Much Hadham in Hertfordshire, tells us how fashions in pottery and trading routes changed in the third century. The mortaria used in their kitchens likewise came to Gestingthorpe from across Southern Britain. One piece, produced in Colchester around A.D 160-200 bore the name of the potter Martinus II. Of additional local interest was some Samian pottery which had also been made at Colchester.

Whilst the villa’s occupants were clearly, ‘pleasantly well off’, the absence of any significant silver and absolutely no gold objects implies that they were not people of ‘lavishly spectacular’ wealth. That the villa had no mosaic floors – nor curiously any oil lamps – further supports this view. Most probably, the inhabitants were of mixed blood or even Celtic origin, who worked hard to preside over a farming estate, with the villa rather like a medieval manor house, or a village’s ‘Big House’ in Victorian times.

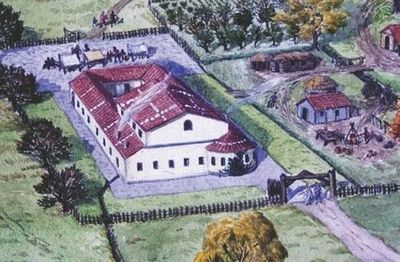

As the years passed, a picture slowly emerged. It was of a settlement extending over about three hectares, with blacksmiths, carpenters and craftsmen’s workshops, a farmyard area and artisan’s huts all centred around a large ‘villa’ type building. The latter had a ‘hypocaust’ heated main room, a bath block, glazed windows and some decorated walls.

Rectangular in shape, the villa was thirty six metres in length and eighteen metres wide. (Roughly the same size as St. Peters Church on Sudbury’s Market Hill.) Two rows of wooden columns supported the villa’s roof – rather like a church with two aisles – although there may have been a small open courtyard at the northern end. The roof was unusual, for there were some white tiles amongst the more typically orangey-red tiles. Both were almost certainly made locally. (Gestingthorpe has a seam of clay which produces white bricks.) The villa’s roof tiles, we have calculated, would have weighed somewhere between thirty to forty tonnes.

The building appears to have been constructed between A.D 175-200, close to the position of an earlier dwelling which was destroyed by fire. (Coincidentally, a number of other Roman settlements in Essex also suffered fires at about this time.*) The owners must have prospered however, for some years after the rebuilding occurred, a heated semicircular ‘best room’, was added to the south eastern corner.

Items of their jewellery such as bronze brooches, finger rings and bracelets were found in the villa and nearby ditches. So too was an almost complete necklace, jet and bronze hairpins, and fragments of glass bowls and beakers. But there was another potential source of income. The major Roman road that ran from London – Chelmsford – Braintree – Long Melford to the North Norfolk Coast, passed through or very close to the Gestingthorpe site. Quite possibly then, the settlement might have provided refreshment, rest and blacksmithing skills to State Officials or any other travellers as they passed along the road.

That the villa is situated almost exactly midway between the River Colne and River Stour suggests there may have been forethought in planning its location. (It is approximately ‘one hours walk’ from both Roman Long Melford and the River Colne.) Ideally positioned to also act as a local administrative and market centre, the settlement could have been pivotal to people in the vicinity.

Inevitably, coins were lost in the transactions and activities of daily life, and over five hundred have now been discovered. Almost all are bronze or ‘silver washed’, with low or moderate value denominations – such as one would expect to find in a ‘working roadside settlement’. Pleasingly however, almost all the major Emperors – such as Claudius, Hadrian, Marcus Aurelius and Constantine – are represented in the coin list.

As the fortunes of the empire declined in the fourth century, so too did the currency. The latest, clearly dateable coin recovered from Gestingthorpe, was minted between A.D 388-392, when Arcadius had been appointed a Caeser (or heir) by his father, Theodosius the Great. Several other ‘minims’, however, are so illegible and tiny, (just 5mm in diameter), that they could well be contemporary or slightly later. The settlement clearly continued until this date, and probably for some decades after the ‘official end’ of Roman authority in A.D 410. Yet a mystery remains. For at some point in the fifth century the settlement was completely abandoned, and then lost for fifteen hundred years.

The Distribution Map of coins lost in more prosperous times is of particular interest. Just to the north of the villa were found some fifty coins, scattered amongst a cobbled area about the size of a tennis court. This is where the market may have been held, and where those from neighbouring Celtic homesteads would have come to buy specialist items, or to sell their own surplus produce. That a cobbler periodically set up his last there is indicated by the discovery of a wide circle of hob nails covering about a metre and a half in diameter.

Within the proximity of the villa were made some particularly exciting finds – such as a beautiful enamelled millefiori ornament. The latter consists of hundreds of minute, coloured glass rods fused onto a bronze base about 35mm in diameter. (Millefiori means a thousand flowers.) A signet ring with an onyx intaglio depicts a lion attacking a red deer – a not uncommon device seen in jewellery and mosaics across the Roman world from Syria to Verulamium (St. Albans). A miniature representation of Cupid, carved in ivory and measuring just six centimetres in height, is thought to have fitted onto the corner of a casket – such as a jewellery box.

It is always tempting to dwell on eye-catching discoveries like these. Yet the far greater significance of Harold’s work was to spot – and retain – much less spectacular artefacts. Some have shed invaluable light on how the ordinary people of our Colne-Stour countryside lived in Romano-British times, and how their craftsmen worked.

To elaborate; two lumps of burnt clay were exposed, not far from part of a bronze worker’s crucible. They came from a mould which had produced a small bronze statuette. Together with part of the ‘sprue cup’, (into which the molten bronze was poured), they were the very first evidence that bronze statuettes had been made in Roman Britain using the ‘lost wax’ process. (The figure, which is thought to be Bacchus, stood about fifteen inches tall.)

A scatter of charred grains, discovered almost three feet beneath the soil’s surface, revealed that Rye, six row Barley and, possibly, Oats were among the crops being grown at Roman Gestingthorpe, in addition to much larger quantities of Spelt and ‘free threshing’ bread Wheat. (The latter is like today’s wheat – which releases its grains far more easily than the earlier hulled wheats like Spelt.)

One shard of pottery bore a small ‘feather shaped’ imprint about two centimetres in length. It had been formed, magnification revealed, when a piece of flax sacking was pressed against the pot’s soft surface before it was fired. Even the ‘half basket weave’ could be identified. Another piece of blackened pottery came from a chimney. When the sooty deposits were analysed they confirmed that pork fat, olive oil and wine had been used in the villa’s kitchen when cooking.

In 1975, the Villa Site was scheduled as an Ancient Monument, and excavations on the field ceased. Many of the finds were temporarily sent away for analysis by twenty eight archaeological experts. Their reports were published by Essex County Council – and made fascinating reading. (See Excavations at Hill Farm, Gestingthorpe, Essex: East Anglian Archaeology Report no. 25).

The iron tools such as carpenter’s chisels, axes and plough shares, for example, were subject to pioneering analysis. The results were surprising: the blacksmiths at Roman Gestingthorpe, and across Britain generally, were unable to ‘heat treat’, (or harden), iron tools and knives as successfully as their Saxon successors. Sophisticated ‘barb spring’ padlocks, however, were being made. Indeed, the most numerous iron objects to be discovered, (apart from some 4000 nails), were keys and locks which were clearly being made – and sold – at the site.

Bone and antler was also being worked. Tools, knife handles, gaming counters and hairpins have all been discovered. Some of the latter were unfinished. That a Gestingthorpe family were making bone hairpins with intricate ‘cross-hatched’ and decorated heads, provides another glimpse into life at the settlement.

Within the theme of ‘How people lived’, we might also enquire, ‘What did they Worship?’ A broken statuette of Venus, made of white clay, was unearthed in the villa. As noted, bronze figures of Bacchus were made nearby. Of equal interest however, was the discovery of two tiny votive axes. One was made of bronze, (with the axe’s ‘head’ being just 7mm wide). The other was produced in lead, as was a miniature scythe. All three, the Report suggests, were probably symbols of a ‘local agricultural Celtic divinity’, which was worshipped at the site. These votive objects, the Report continues, were probably made by the settlement’s own metal worker.

Christianity was also represented. A bronze brooch, which is shaped like a fish and has indentations to indicate the gills, was unearthed near one of the ditches. Even more remarkable, the Sign of the Fish is scratched onto a ‘flue tile’, used in the villa’s hypocaust heating system.

The theme of ‘How people lived before our time,’ has continued to inspire intensive archaeological field walking and historical investigations across the farm since the Report was published in 1985.

In a Roman context, this has resulted in the discovery of two further Romano-British settlements. Both are in Bulmer and both along the presumed line of the Roman road from Braintree to Long Melford. The first is situated just 600 metres north-east of the Villa, (on ‘Old Barn Field’.), the second lies some 650 metres further distant, close to ‘Lower Houses’. (It is even more noteworthy to record that a third site in Bulmer, close to the present day Brickyard, is also about 600 metres from the villa.)

Although the ‘Old Barn Field’ site is so close to the Villa settlement, it provides a dramatic contrast with its neighbour. A Romano-British occupation area, extending over at least 100 square metres, is crossed by a series of ditches. In annual excavations, these have produced extensive quantities of pottery, but almost no personal artefacts or jewellery and only two first century coins. The mystery is enhanced by the unearthing of small amounts of prestige Samian ware, tile and oyster shells.

This paucity of ornaments and metal objects stimulates many questions. Might ‘Old Barn Field’ have been a slave area, or a drover’s compound? Might another craft activity have been conducted there, which we have yet to identify? Was it abandoned after the first or second century? Or is it just one example of a basic, rural dwelling of which there may be many thousands more? That we had farmed both new sites for almost twenty years, before discovering either, is noteworthy in itself.

From the work undertaken on the farm, and in the locality generally, it is becoming apparent that there were numerous other Romano-Celtic homesteads scattered across our area. Can it be argued that the population of our genuinely rural parishes, in the Colne-Stour Countryside, was possibly much the same in A.D 300 as it was in A.D 1700?

On New Years Day 2012, my Father and I drove up to the site of the Roman Villa, which he had so assiduously excavated in the years of my childhood. Today, the settlement is ‘grassed over’ as part of our Higher Level Stewardship Scheme. The villa’s rooms, however, are marked out, so that visitors and school children can appreciate its size and location. Frequently, visitors comment on the site’s remote hilltop situation and extensive views—which stretch across to Bulmer Brickyard, Wickham St. Paul’s and Gestingthorpe.

As my Father and I stood there, I hoped that visitors in the future would continue to enjoy the site’s rural ambience; and that in gazing out over our countryside will still be able to imagine how it might have been in Romano-British times, eighteen hundred years ago.

Ashley Cooper

Ashley Cooper is the author of five local history books, including The Long Furrow and Our Mother Earth. All are available in local bookshops. Excavations at Hill Farm, Gestingthorpe, Essex: (E.A.A. 25): Published by Essex County Council, 1985

Footnote:

*Roman Essex: by Warwick Rodwell. Published by Essex Archaeological Society, 1972.

Gestingthorpe Roman Villa and Local History Museum welcomes about twelve groups of adult visitors each year. A forty five minute DVD which records the story of the excavations and discusses some of the finds will shortly be available. (Initial price £10) To visit the museum or order a DVD, please telephone 01787 462027.

Artists impression, by Benjamin Perkins, of Gestingthorpe Roman Villa.

What we had for dinner.....

...in Bulmer and Gestingthorpe 2000 years ago

For some years, a number of Gestingthorpe residents have been helping at an archaeological excavation, of a probable farmstead in Bulmer, dating to Romano-British times or earlier. The site is about 450 meters from the Gestingthorpe parish boundary and some 600 from Gestingthorpe Roman villa.

The bones from the excavation allow us to glimpse the type of animals which our Celtic forbears were farming—and later eating in their thatched roundhouses. Gestingthorpe almost certainly had similar farmsteads—in addition to the villa—and the bones enable us to imagine our countryside as it was then.

We can’t say when the earliest bones were deposited—but they may predate the birth of Christ. We do know however, that the site was in existence by the mid- late first century A.D. and that some inhabitants would have been alive at the time of the Emperor Hadrian. (A.D 117-138.)

In total some 436 bones and teeth were unearthed, including 54 oyster shells. Whether the latter we eaten at the farmstead or were refuse from the nearby villa is not known.

Cattle, (or cattle sized), bones were significantly the most numerous. Bones from pigs however were surprisingly scarce.

Cattle or cattle sized bones…………….……252…….57.80 %

Sheep, goat or sheep sized bones…………….79…….18.12%

Pig……………………………………………...6…….. 1.15%

Horse…………………………………………...7……...1.61%

Rabbit…………………………………………..2……...0.46%

Non identifiable……………………………….35……...8.04%

Oyster Shells.....……………………………… 54…….12.47%*

The professional zooarchaelogist, Vida Rajkovoca, who analysed the bones, remarked upon the lack of bones from birds or red deer. The two rabbit bones, she says that, ‘are presumably of later date, as there is a general belief that rabbits were a Norman introduction.’

The bones also give us a glimpse of domestic cooking. Joints of beef were being immersed in salt brine to be cured. (As indicated by marks on two of the cattle bones.) Other bones were being split to remove the marrow, whilst butchery marks could also be seen.

A bone from a young horse is of particular interest, as similarly aged horse bones have been found elsewhere in East Anglia. (One of the horse bones analysed was under 15 months of age.)

As mentioned, only 6 pig bones were found. However, one of the most interesting discoveries was a complete Boar’s skull. We think it may have been placed on top of a wooden post— like a totem pole—as remains of a post hole were found next to it.

TENTATIVE CONCLUSIONS

We have a glimpse of a possible farmstead, close to Gestingthorpe’s Roman villa in late Celtic/ early Roman times. We can imagine meadows being grazed by cattle and sheep, while much smaller numbers of pigs were also kept.

On the evidence from this site, the meat diet consisted principally of beef, mutton or lamb. The oysters, whose shells were deposited in one ditch may—or may not—have been eaten by the occupants. The paucity of pig bones is intriguing. One wonders if there might be an explanation! Is there a mystery to solve? It will be interesting to see if this statistic is reflected on other archaeological sites in the area!

Ashley Cooper

Acknowledgments

Assessment of Faunal Remains from Hill Farm, by Vida Rajkovoca, made in 2016 , 2108, 2020.

Interim Report…Excavations Undertaken by SVCA volunteers at Old Barn Field, Bulmer, Essex, 2016-2018, by Corinne Cox

The Gods of Roman Britain, by Miranda J. Green, published by Shire Archaeology 1983.

Photo Gallery

Artists impression of the villa owner’s wife wearing some of the jewellery discovered during the excavations. © Benjamin Perkins